In 1775, opium made its way to the U.S. In the 1800s, opioids were used to treat everyday ailments, from coughs to chronic pain. During the U.S. Civil War, doctors commonly prescribed them to treat soldiers.

By the late 1800s, opioids were available over-the-counter. Bayer brands started selling heroin for pain relief and coughing. As a result, there was a sharp rise in opioid addiction, and by the early 1900s, Americans were crushing pills and inhaling them recreationally.

Introducing the Harrison Narcotic Act.

In efforts to limit the recreational use of opioids, congress passed the Harrison Narcotic Act of 1914, making opioids only available by prescription. The act required anyone who sold or distributed narcotics to register with the government and pay a small tax. Importers, manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, and physicians also had to keep a small record of their transactions, which was available by government inspection.

A vague clause in the act said that doctors could prescribe opioids “in the course of their professional practice.”

Law enforcement interpreted the clause as doctors could not prescribe opioids to addicts because addiction is not a disease. As a result, many doctors were labeled as criminals and put in jail.

The 1980s: Attitudes About Opioids Begin to Change

In the 1980s, attitudes about opioids began to change. Pain specialists and advocacy groups started raising awareness about the inadequate treatment of pain unrelated to cancer. They also highlighted the underutilization of pharmaceutical opioids. Their message was that there was an irrational and undocumented fear of prescribing opioids, referred to as “opiophobia.” If used appropriately, there was a low risk associated with using opioids for pain management.

In 1980, the New England Journal of Medicine published a letter regarding the safety of pharmaceutical opioids. It briefly reported findings from a study that assessed the side-effects of opioids in hospitalized patients, claiming that out of 11,882 hospitalized patients treated with opioids, only four became addicted.

Pain advocates and large pharmaceutical companies frequently used this information to convince doctors that it was safe to prescribe opioids for chronic pain unrelated to cancer.

Furthermore, large pharmaceutical companies targeted physicians by funding conferences and training sessions promoting opioids. They inaccurately claimed the risk of addiction to opioids was less than one percent.

Opioid Overdose Deaths Increase in the 1990s

Opioid overdose deaths came in three waves. The first wave began in the 1990s when the prescription of opioids to treat chronic pain began increasing.

One reason can be attributed to the introduction of new opioid-based products, like OxyContin. OxyContin is an extended-release formula of a called oxycodone. Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin, marketed the drug as less addictive because it’s released in an extended format instead of immediately.

Pharmaceutical companies, like Purdue Pharma, marketed their drugs aggressively. By lobbying lawmakers, sponsoring continuing medical education courses, funding professional and patient organizations, and sending representatives to visit doctors, opioid prescriptions were at an all-time high.

While doing so, they emphasized the efficacy and safety of the drugs. They also reassured doctors that their drugs had a low risk of dependence. Purdue Pharma knew this was false. The drug was not less addictive than other opioids, and they admitted it in a lawsuit.

Unfortunately, doctors and patients were unaware of this false information of the time.

The second wave began in 2010 when there was an increase in overdoses related to heroin.

The third wave began in 2013. There was a significant increase in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids, particularly those involving illicitly manufactured fentanyl.

Opioid use becomes a public health crisis

It wasn’t until 2017 that the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services declared opioid use a public health emergency. They put together the following five-step plan to combat the epidemic.

- Improve access to treatment and recovery sources

- Promote the use of overdose-reversing drugs

- Strengthen the understanding of the opioid epidemic through better public health surveillance

- Provide support for cutting-edge research on pain and addiction

- Advance better practices for pain management

A Solution to the Opioid Crisis

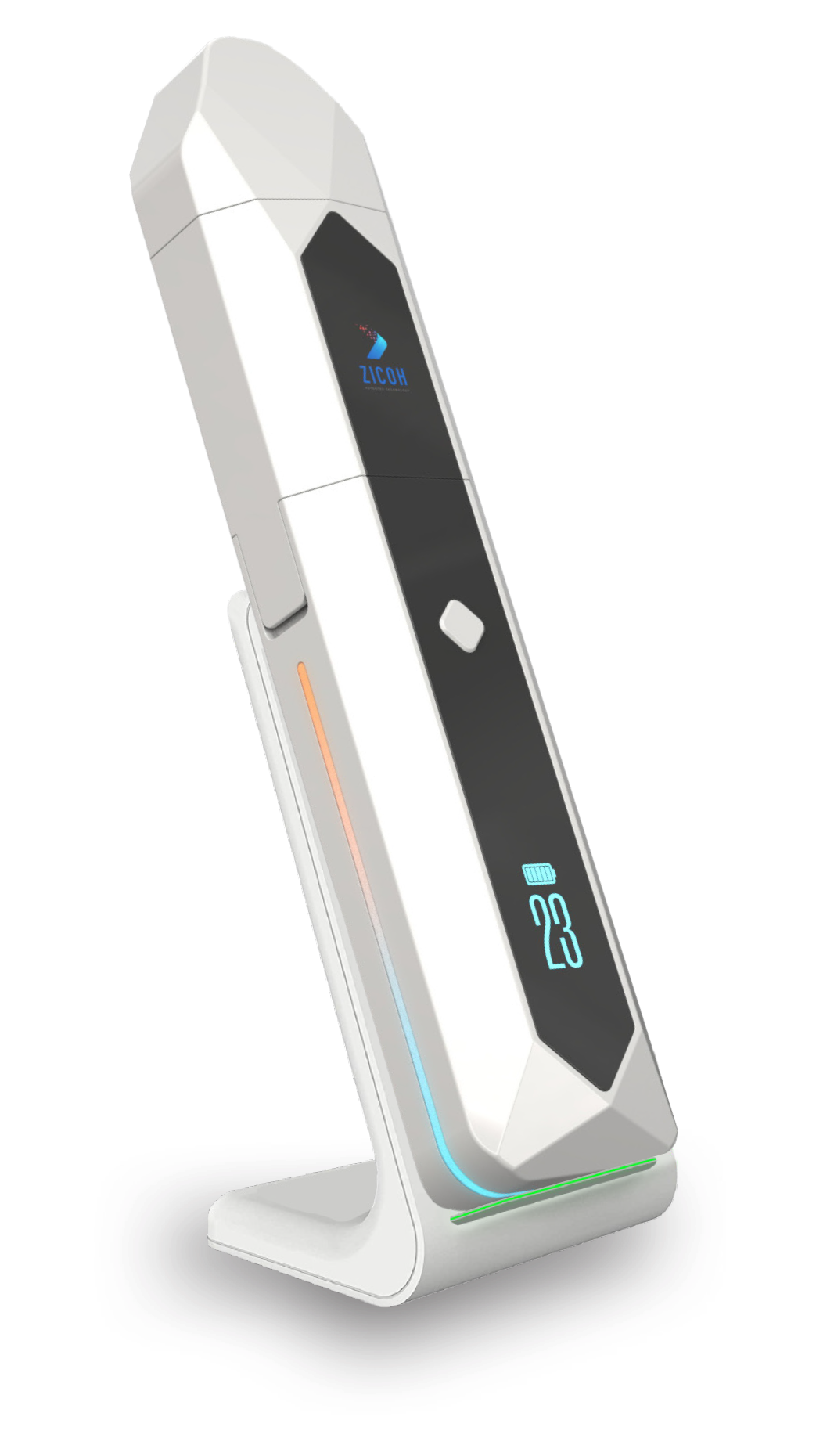

ZICOH will utilize a secure database integrated with AI to form a unique software architecture and advanced patented technology, making it the first device of its kind to enable effective communication through the drug supply chain, from drug manufacturers to wholesalers, distributors, pharmacists, providers, physicians, caregivers, and patients. The device can be programmed to dispense the medication dosage amount, type, and frequency to patients according to the health care provider’s orders and delivery schedule. Each of its features helps ensure patient compliance and patient follow-up, consequentially reducing the risk of addiction and overdose.