The opioid epidemic refers to the dramatic increase in prescription and non-prescription use in the U.S. It also encompasses the opioid-related overdoses that resulted from that increase. Between 1999 and 2018, nearly 450,000 died from an overdose involving opioids.

The opioid-related deaths came in three distinct waves:

- Prescription opioids

- Heroin

- Synthetic opioids

The first wave of the opioid epidemic

The first wave began in the 1900s after doctors started increasing their opioid prescriptions. Pharmaceutical companies informed the public and medical communities that opioids were not addictive.

It wasn’t long before people started misusing their prescriptions.

In 1995, the FDA approved OxyContin, an extended-release opioid manufactured by Purdue Pharmaceuticals. They used aggressive tactics to market the drug as a safer alternative to existing opioids. Because the drug was released slower, they claimed there was a reduced risk of addiction.

Unfortunately, they based their claims on little evidence and OxyContin is just as addictive as other opioids.

“Pain as the 5th Vital Sign”

In 1996, the American Pain Association launched their “pain as the 5th vital sign” campaign. They argued that pain assessment is just as important as assessing the other four vital signs: blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, and temperature.

The Department of Veterans Affairs even adopted the campaign as part of their pain management strategy, giving it more traction.

The problem with pain being labeled a vital sign is that pain is subjective; health care professionals can measure the other vital signs with a medical device.

Around the same time as “pain as the 5th vital sign” launched, pharmaceutical companies also started promoting their drugs for non-cancer-related pain. By 1999, 86% of patients were using opioids for pain that was not related to cancer.

The Joint Commission also contributed to the epidemic. In 2001, they issued standards for assessing pain and claimed opioids were safe. They also insisted pain management was a patient rights issue.

The second wave of the opioid epidemic

Doctors were under much scrutiny for their role in substance use, so they reduced opioid prescriptions. As a result, many users turned to heroin to achieve the same effect or help control cravings or withdrawal symptoms.

All opioids work similarly in the same parts of the brain. When doctors reduced opioid prescriptions, users sought alternatives like heroin. If they were chemically dependent on prescription opioids, they might have turned to heroin to help with cravings or withdrawal symptoms.

Heroin is a highly addictive drug derived from morphine. Not only is it often cheaper and more available than prescription pills, but the effects are also more potent.

Studies have shown that many people who are addicted to heroin started by using prescription pills. These may have been pills prescribed to them for their own pain management or pills that they received from friends or family members.

The third wave of the opioid epidemic

The third wave started in late 2013 and is from synthetic opioids, primarily fentanyl.

Fetanyl is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine. Doctors prescribe it to treat severe pain, often associated with cancer. Because of its high potency, it is usually administered in a controlled setting like a hospital.

Unfortunately, fentanyl is often added to heroin, cocaine, and other illegally manufactured drugs to increase its euphoric effects.

Overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids were nearly twelve times higher in 2019 than in 2013. Most of the fentanyl-related overdoses or deaths are from illegally manufactured drugs.

The current status of the opioid epidemic

The opioid epidemic is complex, and many parties are responsible. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic further complicated the situation. Not only has it triggered new dependence issues for some, but it has also exacerbated existing addictions and disrupted treatment for those already seeking help.

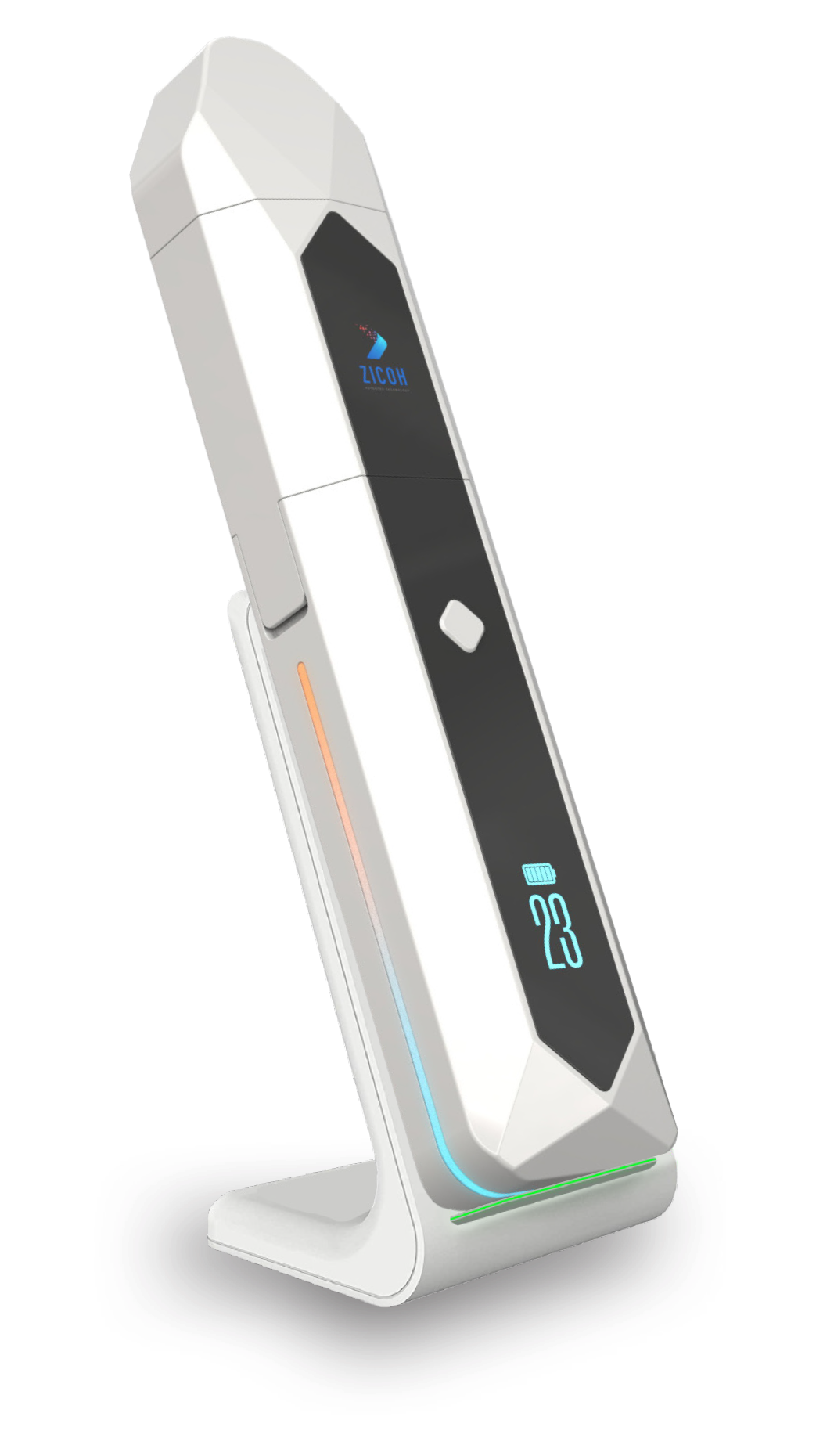

A Solution to the Opioid Crisis

ZICOH will utilize a secure database integrated with AI to form a unique software architecture and advanced patented technology, making it the first device of its kind to enable effective communication through the drug supply chain, from drug manufacturers to wholesalers, distributors, pharmacists, providers, physicians, caregivers, and patients. The device can be programmed to dispense the medication dosage amount, type, and frequency to patients according to the health care provider’s orders and delivery schedule. Each of its features helps ensure patient compliance and patient follow-up, consequentially reducing the risk of addiction and overdose.